Sometimes, when we think about Black History, we think about it as being in the past. At Phi Theta Kappa, Black History is something we live daily. It is very much a part of our present.

Although we serve community college students from all over the world, Phi Theta Kappa’s Headquarters is located in Jackson, MS—a city some people describe as center of the Civil Rights Movement. Here, in 1961, the Freedom Riders, a group of civil rights activists, were arrested and beaten following their attempts to use white facilities at a bus station. Then, in 1964, Jackson saw the assassination of a young Civil Rights activist named Medgar Evers by a Ku Klux Klan member; earlier that same day, President John F. Kennedy delivered his civil rights address.

Today, over 2 million undergraduate students are Black. This is because, more than 60 years ago, brave Black students risked it all for an opportunity pursue an education beyond high school. They were willing to die, and some did, for a chance to have a better life—not just for their families, but for all Black Americans.

I have met one of these civil rights pioneers: James Meredith, the first Black student admitted to the racially segregated University of Mississippi, lives here in Jackson. From time-to-time, I see him at the grocery store or at a local breakfast spot where he can always be found wearing a bright red University of Mississippi ball cap. But, as a young man, things were different for Black Americans like James.

Inspired by President John F. Kennedy’s inaugural address, James decided to pursue his dream of college. Amid protests and riots, James was escorted onto campus by armed federal troops and US Marshalls. He ultimately graduated and went on to earn a Master’s degree. Today, his granddaughter is a student at the same college.

You may have heard of other Black students from that time, who faced the same barriers and roadblocks that James did. Charlayne Hunter and Hamilton Holmes were the first Black students to attend the University of Georgia, and Vivian Malone and James Hood were the first Black students to attend the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa. While many of us know these names as people who made the way for today’s students, there are others who are less known but just as significant.

Clyde Kennard was born in 1927 in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. At twelve, he followed an older sister north to Chicago to go to school. When he turned eighteen, he joined the military and served for seven years. After receiving an honorable discharge from the Army in the early 1950s, he enrolled at the University of Chicago. Three years into a degree in political science, his stepfather died and Kennard returned to Mississippi to help his mother run the farm.

Hattiesburg was an area where there were no Black colleges, so he applied for admission to the all-white Mississippi Southern College (currently The University of Southern Mississippi). Kennard’s attempt to desegregate Mississippi Southern College was promptly denied and he was warned never to apply for admission again. He refused to adhere to these warnings and wrote letters in the local paper arguing that “merit be used as a measuring stick rather than race.”

As a result, Kennard was framed, falsely accused, and convicted of multiple crimes. Kennard was sentenced to 10 years in prison, ensuring that he never finished college. He died three years later. Efforts to clear Kennard of wrongdoing continued for decades, and on May 16, 2006, Kennard was fully exonerated of the false charges against him. Clyde Kinnard’s story is available from the University of Southern Mississippi.

Today, we can still see the long-term impact the separate and unequal system of education had and continues to have on Black Americans. Black students do not enroll or complete college at the same rates as their white counterparts. At four-year colleges, Black students complete at a rate of 23% less than white students. At community colleges, Black students complete at a rate of 21% less than white students. These gaps are forecasted to further widen due to the disproportionate impact of COVID on people of color.

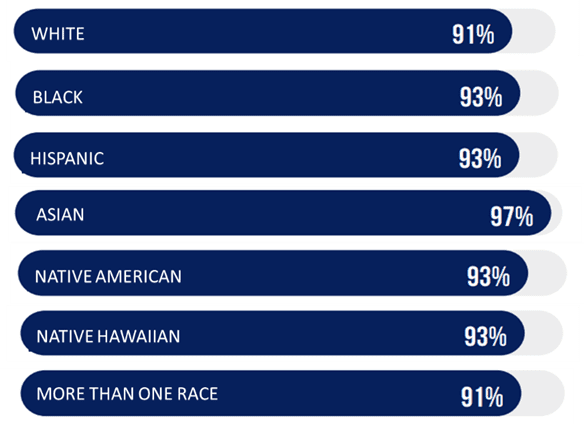

At PTK, I am proud of the work we do to help close racial gaps in degree completion outcomes. Black PTK members have a 93% success rate and are equally likely to succeed as members of other races. We will continue this work, not just during Black History Month, but always—and we will do so because young Black students cared enough to pave the way.

Phi Theta Kappa Student Success Rates by Race and Ethnicity

Dr. Lynn Tincher-Ladner is president and CEO of Phi Theta Kappa Honor Society. Phi Theta Kappa’s mission is to recognize high achieving college students and provide them with opportunities to grow as scholars and leaders. Phi Theta Kappa is recognized as the official honor society for community college students by the American Association of Community Colleges. You can follow Lynn on Twitter @tincherladner.