Editor’s Note: This post was written and submitted by Mariah Mayhugh, 2020-2021 International Vice President for Division 4.

I’ve always loved to write. I wrote my first story when I was 5 years old, complete with a plot, climax, satisfying ending, and my favorite stuffed animal as the main character.

As I got a little older, my writing matured with me and I won my first regional writing contest at the age of 11. The stories and publications grew from that point forward, but I never saw writing as anything more than a fun hobby and English as an easy class in school. Over the past two years, though, that’s all changed.

When I was 7, I was diagnosed with two different types of epilepsy. While going to the hospital and dealing with seizures was hard, what was hardest for me personally was feeling different than everyone else. I felt alone and frustrated that I seemed to be the only one who had to face this. I didn’t want to be different — I wanted to be a normal kid. So, I hid my epilepsy the best I could from everyone outside my immediate family.

For 10 years, the doctors’ appointments, medications, and hospital stays were kept under wraps. I didn’t want anyone feeling sorry for me or viewing me as “the sick kid” — I was determined to get through it and eventually bury it as a piece of my past that I never spoke about.

Until my senior year of high school, when my final English assignment changed everything.

We were assigned to write a 10-page research paper on a topic that interested us but that we knew little about — a challenging prompt meant to encourage us to go out and actually research something new. At the time, I was thinking I would pursue healthcare as a profession and realized I knew nothing about my own condition. That seemed wrong, so “childhood epilepsy” became my topic.

We were assigned to write a 10-page research paper on a topic that interested us but that we knew little about — a challenging prompt meant to encourage us to go out and actually research something new. At the time, I was thinking I would pursue healthcare as a profession and realized I knew nothing about my own condition. That seemed wrong, so “childhood epilepsy” became my topic.

In writing the paper, my whole world was turned upside down. I wasn’t alone. I learned that a staggering one in 26 people will develop epilepsy, and it is the third most common neurological disorder in America. Children with epilepsy often feel alone, isolated, and scared because epilepsy visibility isn’t common. They are three to six times more likely to battle mental health illnesses such as anxiety and depression and twice as likely to attempt suicide. Many of them are told they won’t succeed in school or turned away from colleges or even jobs (even though that’s against the law).

I wanted to gather up each and every child and give them a hug. I wanted to tell them: “Hey, guess what? I had epilepsy when I was your age and now I’m in college! You are going to be just fine. Being different isn’t bad…we all face something!”

That’s when a light bulb went off. Why couldn’t I be a voice for children with epilepsy? It was clearly a cause that needed attention, as one of the most underfunded illnesses in America. And children were suffering psychologically because no one was portraying epilepsy in a positive light. Maybe I could do that.

After so long of keeping silent, it was hard to undo the instinct. But my desire to help children was greater than my desire to pretend I was normal. I was old enough now to realize normal didn’t exist. I wanted to embrace my differences and use them to make a difference.

One of the first events I attempted to host was at my local library. I wanted to do a book reading, followed by a craft and a Q&A session. I started searching the library’s database for books about absence epilepsy, one of the forms of epilepsy I grew up with. I could speak to it personally, and it is very common in children.

But…there weren’t any. That alone was disheartening…if children don’t have easy access to these books, how can they learn and grow? I expanded my search across the Internet, and I grew increasingly frustrated, as every book I found was about one type of epilepsy and had a boy as the main character.

I decided to fuel my frustration into making a change. I certainly knew enough about absence epilepsy; why couldn’t I write a children’s book? I wanted a character who experienced the same sort of epilepsy I did, who had to have an EEG test done, and who was a girl. I also wanted the character to not be “cured” of their epilepsy by the end of the book, as the process of achieving seizure freedom can take months or years and portraying it as a quick fix is harmful to children, who will likely feel disappointed if that doesn’t occur.

I decided to fuel my frustration into making a change. I certainly knew enough about absence epilepsy; why couldn’t I write a children’s book? I wanted a character who experienced the same sort of epilepsy I did, who had to have an EEG test done, and who was a girl. I also wanted the character to not be “cured” of their epilepsy by the end of the book, as the process of achieving seizure freedom can take months or years and portraying it as a quick fix is harmful to children, who will likely feel disappointed if that doesn’t occur.

Taking all these things into consideration, I came up with the character Mimi, a 7-year-old girl with absence seizures who loves playing pretend, eating ice cream, and swinging on the swings. Mimi is just an average girl and the book doesn’t take away from that, but it doesn’t diminish her epilepsy experience, either. She is afraid and even mad. But, the book helps kids realize that you can live a full and happy life with an epilepsy diagnosis.

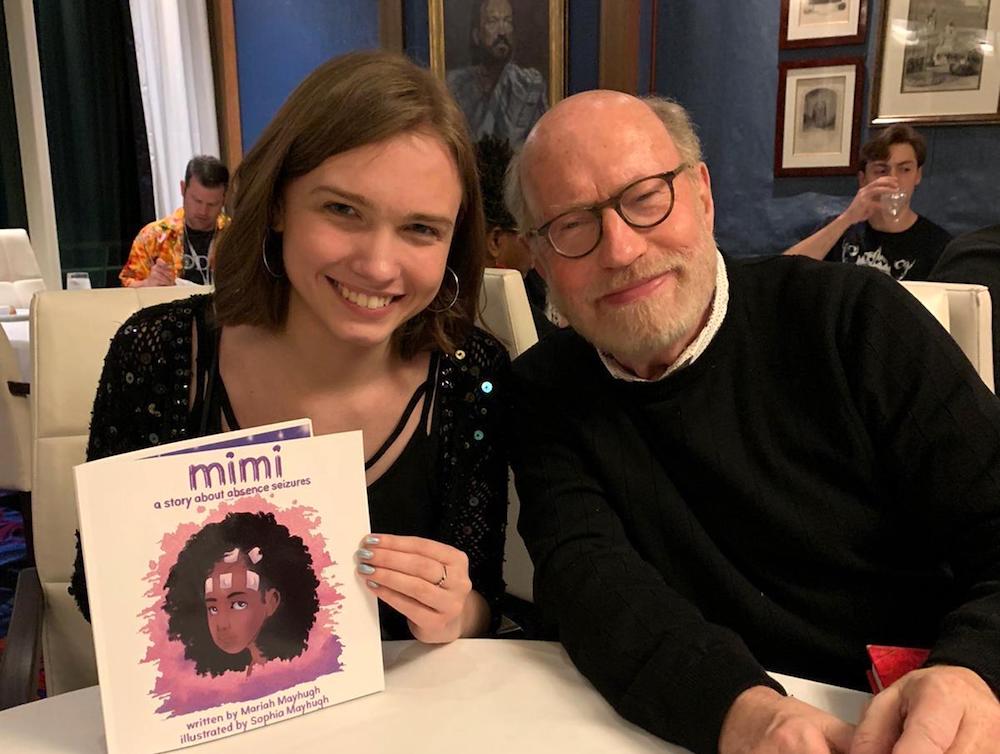

My sister Sophia provided the illustrations, and we received a grant in September 2019 from the Awesome Without Borders Foundation to cover many of the up-front costs and donate some copies to local doctors’ offices. Mimi: A Story About Absence Seizures was published in December 2019, and it soon caught the attention of world-renowned authors and screenwriters. What I thought of as just a small personal project gained global attention in less than a year. I felt like I was dreaming!

In the words of my role model, Malala Yousafzai, “When the whole world is quiet, even one voice becomes powerful.” I am doing everything I can to make a difference for people with epilepsy. If I can effect change for students, children, and even adults in just two years through my writing, I can continue to do all that and more with even more time.

Creating lasting change in your community and in this world is far from easy. I have days I am so stressed out, I don’t even accomplish anything. I have nights I barely sleep. But every morning I wake up ready to go — whether that be challenging my voice through writing, representing my honor society, or volunteering with the Epilepsy Foundation of America. I have realized that my one thing I saw as a defect, a setback, has actually made me a stronger person and has allowed me to create change for people across the country.

I know we’re all facing some sort of struggle, some sort of setback. Most of us are struggling with COVID and the challenges it has brought us, whether that be loss of a job or loss of a loved one. Maybe you feel like quitting. Maybe you feel like what you have to say just doesn’t matter.

But don’t quit. Don’t give up and never think that your voice and your story don’t matter. I didn’t see myself as a writer, not at first. But writing has allowed me, after over a decade of silence, to use my voice to advocate for others. That is powerful, and we all have a story. Written down or not, we can all use our stories to change the world.

Ten years ago, I was diagnosed with epilepsy. Five years ago, my epilepsy was still a dark secret. Two years ago, I wanted to be an advocate but didn’t know where to begin. Today I am a published author, public speaker, and one of the top students in the country through opportunities in my honor society. While 2020 has taken a lot from me, I will never forget that it was the year I found my voice as a writer — and I will always be thankful for that.